Tony Jouanneau, une approche symbiotique des savoir-faire

Installé au JAD depuis janvier 2024, Tony Jouanneau est designer, artisan et chercheur. Formé au design produit à l’ESAD d’Orléans, il a travaillé pendant sept ans au sein du studio textile Tzuri Gueta où il se forme au métier d’ennoblisseur. Il oriente ensuite sa pratique sur l’éco-conception et le biodesign lors d’un parcours à l’ENSCI-Les Ateliers. En 2017, il fonde L’Atelier Sumbiosis, un laboratoire de recherche en design où se rencontrent les savoir-faire textiles et la science.

En s’inspirant du processus de la symbiose, Tony Jouanneau y réunit chercheurs, scientifiques et artisans pour imaginer une collaboration innovante entre le vivant et les matériaux souples. Lauréat de la Villa Kujoyama, Tony Jouanneau part au Japon de septembre à décembre 2023 pour initier de nouvelles collaborations avec des artisans locaux et mener une recherche sur les colorants d’oursins en partenariat avec la Sorbonne. Dans cet entretien, il revient sur son parcours, sa pratique entre recherche et création et cette expérience de résidence japonaise.

Pour comprendre votre résidence à la Villa Kujoyama, il faut d’abord comprendre comment vous en êtes venu à l’ennoblissement textile et à la recherche. Quelles ont été les grandes étapes de votre parcours jusqu’à aujourd’hui ?

A l’origine, j’ai une formation en design produit. Et pendant mes études, j’ai fait la rencontre du designer textile Tzuri Gueta, qui venait alors de mettre au point un brevet alliant silicone et étoffe, à partir duquel il fabriquait toutes sortes de textures organiques, inspirées du vivant. J’avais toujours eu une appétence pour les matériaux souples car l’une de mes grands-mères était cheffe d’atelier d’une ganterie et j’étais fasciné par l’univers esthétique de Tzuri Gueta.

J’ai travaillé pendant sept ans avec lui. Sept années pendant lesquelles je me suis formé au métier d’ennoblisseur textile, un savoir-faire qui consiste à ornementer des tissus de manière chimique ou mécanique, pour leur donner des caractéristiques esthétiques et techniques. J’étais en charge de mettre en volume les tissus et d’imaginer des mises en application qui allaient du bijou à l’objet en passant par l’installation et l’œuvre d’art.

C’est comme ça que je suis devenu artisan : de manière très empirique, en travaillant avec mes mains au sein de l’atelier.

Toutefois, l’ennoblissement est un monde de chimie parfois nocive. C’est ce qui m’a poussé en 2016 à réorienter ma pratique pour m’intéresser à un domaine émergent à l’époque : le biodesign et la biofabrication, un principe de convergence entre la biologie – qui identifie des principes et des mécaniques du vivant – et le design – qui transfère ces principes dans des applications humaines en pensant la fonction, l’usage et la fabrication.

C’est au cours de la formation que j’ai suivie à l’ENSCI-Les Ateliers que j’ai choisi un principe biologique qui structure aujourd’hui encore ma pratique : la symbiose, qui a donné son nom à mon atelier. Cette notion de symbiose se définit comme l’association d’organismes vivants pour servir les conditions de leur propre régénérescence. Une association qui peut être parasitaire, mais que je prends dans son sens vertueux. C’est cette même notion qui a donné naissance à ma méthodologie et qui guide ma démarche créative au sein de l’atelier : l’association d’un traitement à un tissu dans cette optique symbiotique et écologique.

Aujourd’hui, au sein de l’atelier, j’ai deux activités principales, toutes deux profondément marquées par la notion d’échange et de collaboration : la recherche, en collaboration avec des chercheurs, et la création, en collaboration avec des artisans. En parallèle, je consacre aussi un pan de mon activité à la transmission.

C’est en grande partie sur votre activité de recherche que s’est construit votre projet de résidence à la Villa Kujoyama. Pourriez-vous nous en dire un peu plus ?

Le volet recherche de mon activité se concentre sur des ressources biologiques régénératives, des micro-ressources, qui ont un potentiel à investir dans le champ de l’ennoblissement textile et de la biofabrication. Je cherche en effet à comprendre si ces ressources biologiques pourraient apporter une réponse à un savoir-faire d’ennoblissement qui présente des pollutions. Ainsi, chaque projet de recherche se concentre sur un savoir-faire spécifique et sur une hypothèse créative autour d’une ressource biologique. C’est ainsi que j’ai mené plusieurs recherches autour d’applications de colorations textiles à partir de micro-algues, de micro-champignons, de l’impression bactérienne sur tissus, ou encore de techniques de dévorage avec des insectes sur des velours de soie.

Ces recherches, je les mène en collaboration avec des ingénieurs biomatériaux, comme Christophe Tarabout, ou encore Marie Alberic, chercheuse au CNRS de la Sorbonne Jussieu. C’est cette dernière qui m’a proposé de travailler sur l’extraction pigmentaire des squelettes d’oursins et l’application de ces pigments et colorants sur des tissus : le projet qui a fait l’objet de ma résidence à la Villa Kujoyama, au Japon.

Quels étaient les objectifs de cette résidence ?

Ce projet, ECHIRO du latin echino – l’épine – et du japonais – iro – la couleur, est à l’origine de ma candidature à la Villa Kujoyama, tout d’abord parce que le Japon est le premier consommateur au monde d’oursins et qu’il possède donc un important gisement de matière première à revaloriser. Cette résidence avait donc un premier objectif : celui de remonter une filière du déchet d’oursin. Le second était de faire dialoguer cette recherche innovante avec des savoir-faire ancestraux de coloration textile japonais, par la rencontre avec des artisans locaux.

En ce qui concerne mes recherches sur la filière de déchets d’oursins, je me suis concentré dans un premier temps sur la récolte d’épines sur les marchés au poisson, ce qui m’a amené progressivement aux conserveries. C’est ainsi que j’ai trouvé une entreprise à l’ouest du Japon, Ozuka Suisan, qui s’intéressait depuis 15 ans déjà à la valorisation de ses déchets par la couleur et à qui j’ai présenté l’objet de ma recherche.

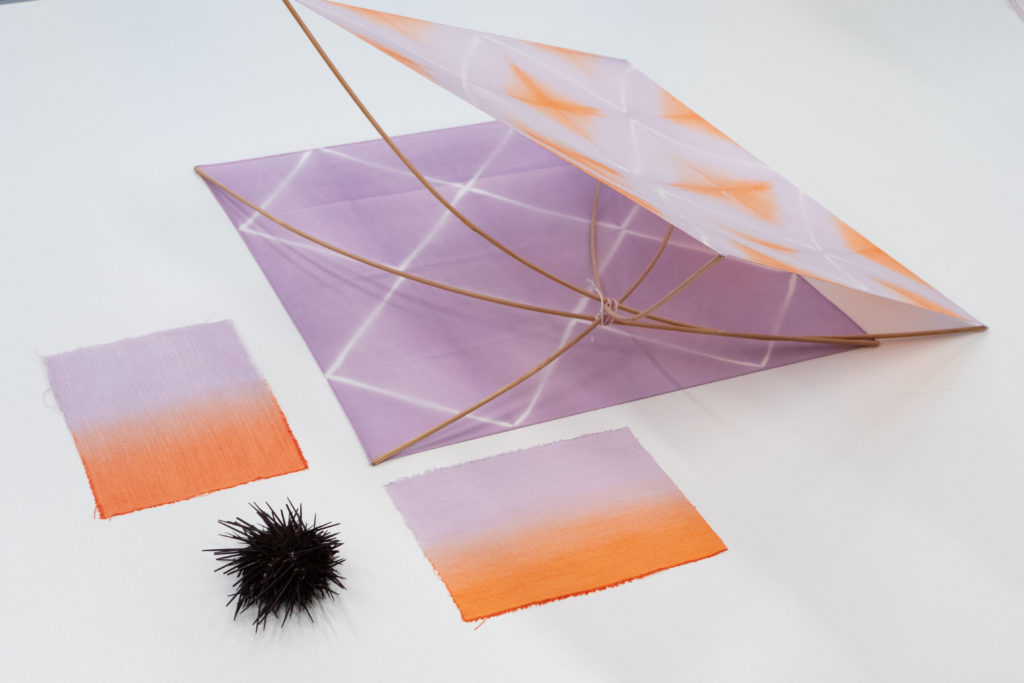

Le reste de ma résidence a ensuite été consacré à la rencontre avec des artisans. L’idée était de faire dialoguer des savoir-faire pour conférer à des tissus des jeux graphiques ou volumiques visant à mettre en avant les nuances d’oursins. J’ai ainsi exploré plusieurs pistes de collaboration comme le shibori, une technique de ligature sur tissu pour créer des motifs graphiques ou volumiques avec Maître Kuno de la Kuno Factory à Arimatsu. Puis, je suis allé dans la région d’Okinawa, sur l’île d’Amami, pour découvrir un savoir-faire ancestral, le dorozome, une technique de teinture mordancée à la boue. J’ai fait la rencontre, dans la région du Kansai de Takeshi Nakajima spécialisé dans la technique de l’hikizome, une technique de peinture sur soie à la brosse. J’ai aussi échangé avec Taketoshi Akasaka qui pratique le katazome, une technique de teinture au pochoir en pâte de riz. Certaines de ces rencontres ont été particulièrement émouvantes, comme celle d’Akiko Ishigaki sur l’île d’Iriomote, la plus au sud du Japon ; cette femme crée ses tissus de bout en bout, partant de la fibre de bananier qu’elle file, tisse puis teint avec des colorants végétaux fixés par l’eau de mer dans un chemin bordé de mangroves.

Pendant ces quinze semaines, les artisans que j’ai rencontrés m’ont ouvert les portes de leurs ateliers, m’ont partagé leur connaissance et leurs savoir-faire, me laissant entrevoir avec eux de belles perspectives de collaborations que j’aimerais pouvoir présenter dès 2025.

Comment est-ce que cette mise en lumière des savoir-faire, qu’ils soient français ou japonais, guide votre pratique de création ?

Il est très important à mes yeux de valoriser les savoir-faire grâce à des créations d’exception, l’innovation, l’hybridation, car cela nous invite et nous pousse à porter un regard neuf sur l’artisanat.

Sur le plan formel, c’est à travers des mouvements organiques que je cherche à sublimer les techniques et savoir-faire ancestraux avec lesquels je travaille, car je suis attaché à leurs caractères instinctif et sensoriel qui appellent la main et le toucher. Et puis, comme je l’expliquais plus tôt, il y a ce principe symbiotique, et la rencontre formelle entre deux couleurs, entre le liquide et le tissu, etc.

Chaque année, j’essaye de m’approcher de nouveaux artisans pour des collaborations. C’est cette démarche que je poursuis depuis 2017 et qui m’a conduit au JAD. Se rassembler, mutualiser les pratiques et les hybrider, est une force à mes yeux. Une logique d’entraide et de partage qui va à l’encontre de la culture du secret qui a longtemps eu cours dans le domaine des métiers d’art.

Enfin, la transmission tient aujourd’hui encore une place importante dans votre activité.

L’Atelier Sumbiosis est né par la transmission, et bien que la création ait progressivement pris de plus en plus de place, je reste attaché à l’idée de transmettre, qu’il s’agisse d’étudiants comme à l’ENSCI-Les Ateliers ou de professionnels du secteur de la mode comme à l’Institut Français de la Mode. Enfin, récemment, dans le cadre du partenariat du JAD avec l’Académie de Versailles, j’ai proposé à des enseignants de l’Académie une formation d’une journée autour de l’ennoblissement naturel. Une journée thématique à travers laquelle j’ai invité les enseignants à tisser des liens entre cette discipline et leurs matières, afin d’amener les élèves à s’intéresser au textile durable à travers ce qu’ils portent, comment ils le portent et pourquoi ils le portent.

Propos recueillis par Brune Schlosser

Chargée de projets culturels et patrimoniaux à l’INMA et correspondante de l’INMA au JAD

Sur la même thématique

Juana García-Pozuelo, rencontre entre l’idée et la main

Lucie Ponard, l'écologie des matériaux

Matière à Penser, un programme d'excellence dédié aux métiers d'art