Juliette Green : Que ressent-on quand on crée quelque chose ?

Juliette Green est une jeune artiste plasticienne française, installée au JAD depuis avril 2023 dans le cadre d’une résidence de création menée en partenariat entre le Salon de Montrouge et le Département des Hauts-de-Seine.

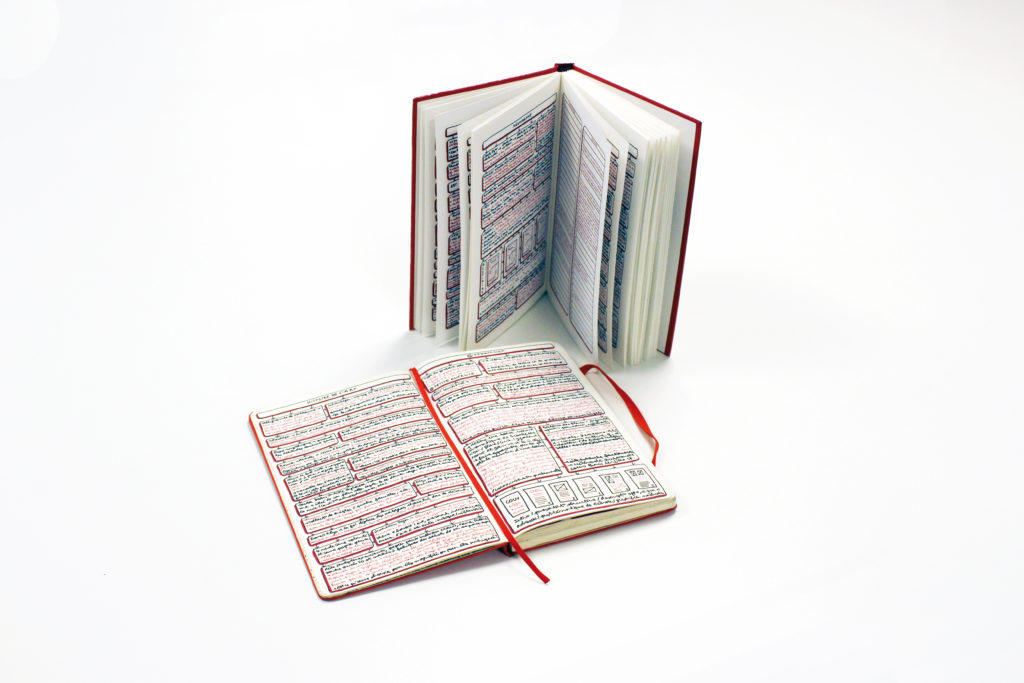

Pendant son adolescence, Juliette Green a mis au point une méthode pour prendre des notes à l’école en mélangeant textes et dessins. Elle s’en sert désormais pour raconter des histoires dans ses œuvres. L’artiste plasticienne se penche aujourd’hui sur le JAD pour nous raconter son histoire passée et présente.

Juliette, tout ton univers artistique se base sur un système de création singulier. Est-ce que tu veux bien commencer par nous le présenter ?

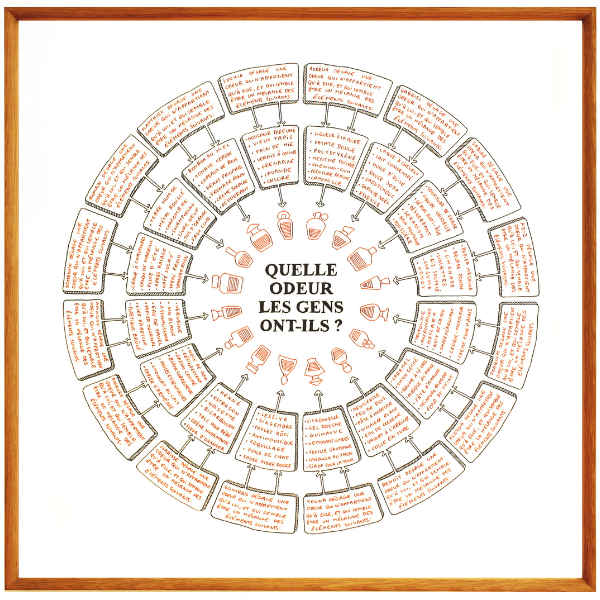

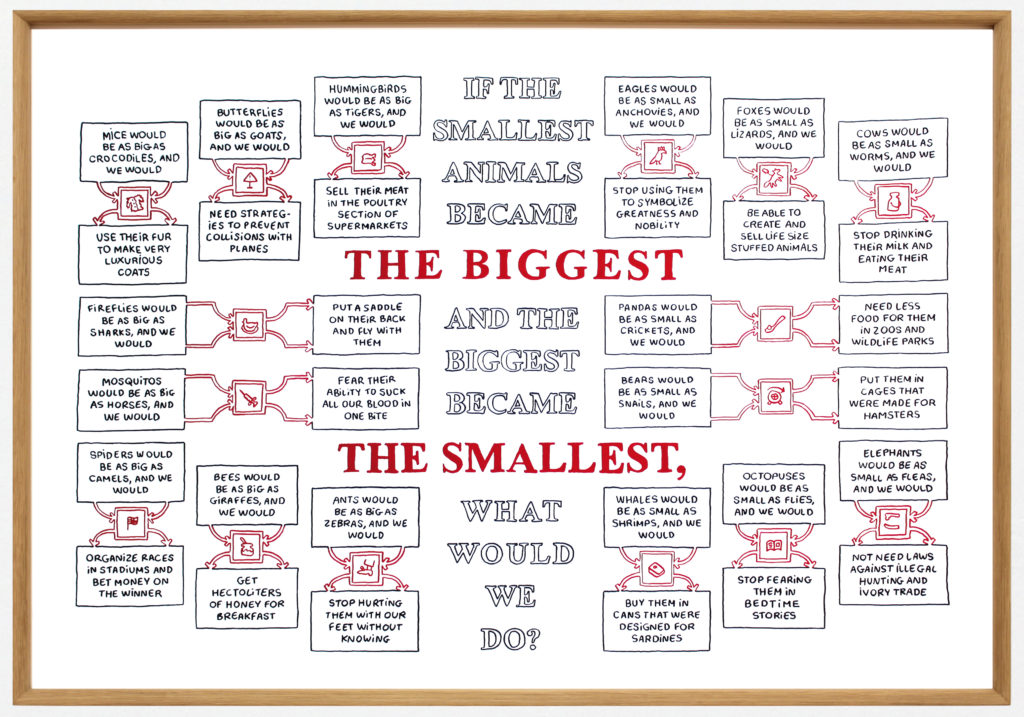

Ma pratique est à mi-chemin entre l’écriture et le dessin. Les œuvres que je crée racontent des histoires qu’on peut lire en suivant un système de flèches. Ces récits ont généralement une question existentielle pour source d’inspiration, qui est écrite en grand sur l’œuvre et lui sert de titre. Au-delà de ces textes, il y a de nombreux éléments visuels : des croquis, des personnages, des pictogrammes, des plans d’architecture, des cartes, etc.

Ce procédé, tu le mets au point assez tôt pendant ta scolarité. Comment ce qui n’était au départ qu’une méthodologie de travail est-il devenu le processus créatif central de ton art ?

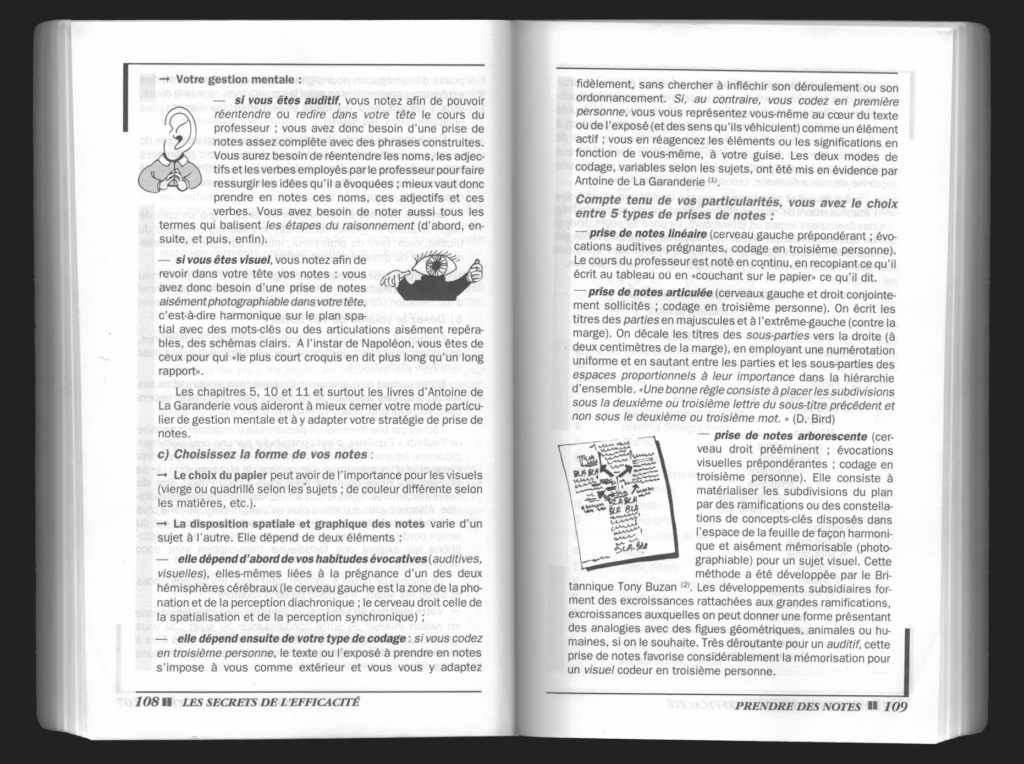

En effet, c’est à l’école que tout a pris forme. J’ai lu un manuel de conseils pour améliorer ses méthodes d’apprentissage scolaire. L’auteur recommandait d’ajouter des éléments dessinés dans les notes qu’on prend dans les cours pour faciliter la mémorisation. J’ai appliqué ce conseil dès le premier cours que j’ai suivi au lycée. Ce n’était pas possible auparavant car l’équipe enseignante n’avait pas les mêmes attentes.

Au collège, nous devions suivre des consignes de mise en page plus standardisées : écrire sur des feuilles avec des lignes, souligner chaque titre, utiliser telle couleur pour les exercices, noter le plan du cours à la lettre, etc. J’ai pu développer mon propre système de prise de notes à partir du moment où nous avons eu davantage de liberté. Plus tard, ce travail a évolué : je suis entrée dans une école d’art et j’ai pris un tournant narratif. Les textes à partir desquels je dessine sont devenus des récits.

Tous tes dessins ont une histoire à part entière. Il y a notamment ces phrases, ces questions qui en orientent la lecture. On qualifie parfois tes dessins d’arbre sémantique, comment se construit ce travail autour des mots dans les architectures visuelles que tu imagines ?

Certaines personnes parlent d’arbres sémantiques, de cartes heuristiques, de cartes mentales, de schémas, de diagrammes… Il y a beaucoup de dénominations pour ces formes visuelles qui sont partout autour de nous. En temps normal, elles ont une fonction utilitaire : elles apportent des informations.

Les employer pour raconter des histoires est inhabituel mais comme nous rencontrons souvent des structures de ce type dans la vie courante, nous savons instinctivement comment les aborder. Leur aspect est familier. Nous savons quel est leur fonctionnement et leur mode de lecture.

Quel cheminement t’a mené au fait de t’autoriser à laisser davantage de place au dessin ?

Sa quantité varie d’un projet à l’autre : pour certaines œuvres, j’aime que le dessin soit prépondérant et pour d’autres, je préfère que ce soit le texte. Cependant, ils m’intéressent beaucoup moins lorsqu’ils sont seuls : faire un projet d’écriture sans aucun élément visuel (par exemple, rédiger un livre) n’est pas ma vocation. Faire des dessins sans texte ne m’attire pas non plus. Peut-être que je changerais de point de vue au fil du temps. Je ne me l’interdis pas mais pour le moment, j’ai le sentiment que ma place est à la frontière entre ces deux moyens d’expression.

Tu en es également venu à la performance, à travers le recueil de paroles auprès du public pour réaliser des créations en direct. Le résultat final est toujours si soigné. J’ai notamment en tête, l’œuvre que tu as réalisée en une heure lors de la rencontre du JAD du mois de mai avec le designer Tony Jouanneau. Comment le processus de création s’opère-t-il dans ce contexte ?

L’oralité a fait partie de mon travail pendant des années. Quand je prenais des notes de cours, tous les textes étaient ceux que prononçaient mes professeurs. J’ai perdu ce lien avec la parole à mon arrivée aux Beaux-Arts : j’ai commencé à inventer les textes de mes œuvres moi-même, sans m’appuyer sur ce que j’entendais. C’est après mes études que j’ai renoué avec le son.

Une commissaire d’exposition m’a invitée à dessiner en direct au Palais de Tokyo pendant un cycle de conférences. Mes automatismes de prise de notes sont revenus grâce à ce projet. J’ai retrouvé le plaisir que je ressentais quand je transcrivais les paroles d’autres personnes en diagrammes. C’est exactement ce qui s’est produit pendant la rencontre avec Tony Jouanneau : c’était agréable de l’écouter parler de son métier et de ses projets, puis de transformer ses mots en une forme visuelle. Cet exercice demande une concentration et une attention extrême.

Tu avais déjà participé à de nombreuses résidences par le passé. En arrivant en avril dernier au JAD, quel était ton projet ? Comment construit-on une œuvre en quelques mois, à partir d’un lieu, d’une histoire ?

En arrivant au JAD, je savais qu’il me faudrait un temps d’adaptation car habituellement, je travaille dans le milieu de l’art contemporain. Le design et l’artisanat d’art n’étaient pas des mondes que je connaissais de près. La première phase a donc été de me familiariser avec ces métiers en écoutant les gens en parler, dans des moments dédiés ou dans des moments informels.

J’ai posé beaucoup de questions aux créateurs du JAD sur leurs parcours, leurs choix de carrière, leurs modes de travail et d’organisation, leurs projets. J’ai pris des notes. J’ai visité leurs ateliers et les expositions du JAD, j’ai participé aux événements et puis j’ai découvert les alentours, notamment le musée voisin. Je me suis renseignée sur l’histoire du bâtiment grâce à l’équipe de médiation, qui proposait des visites guidées. J’ai également parlé avec les personnes qui gèrent le lieu, pour bien connaître ses enjeux et son positionnement. Ces moments ont été importants pour cerner le contexte de la résidence.

Au JAD, c’est au sein de l’atelier 108 que tout se passe et de manière très confidentielle. Je suis curieuse de savoir quelles sont les questions et grandes thématiques qui guident ton travail depuis ton arrivée en avril dernier.

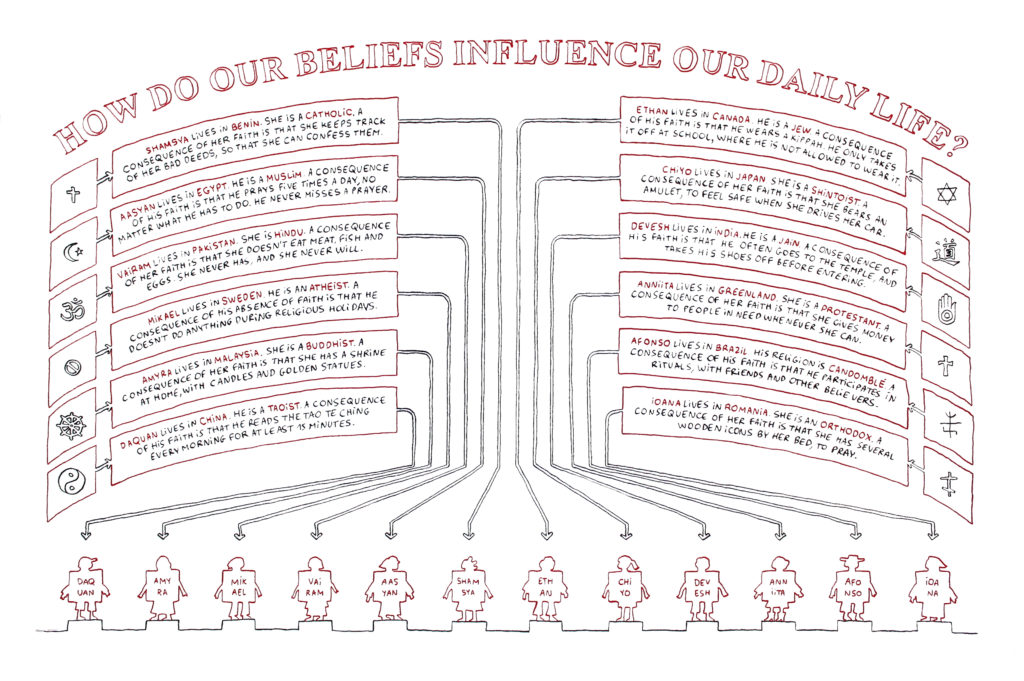

J’ai longuement réfléchi au sujet de mon projet final parce que je tenais à ce qu’il soit accessible : je voulais qu’il puisse être compris par des gens qui ne sont pas spécialistes du design ou de l’artisanat. C’était primordial à mes yeux car le JAD est fréquenté par un public très diversifié, à la fois professionnel et non professionnel. En définitive, j’ai choisi de me focaliser sur ce qu’on ressent quand on crée quelque chose. Tout le monde a déjà fait l’expérience de la création. C’est une situation que chaque être humain connaît au moins ponctuellement, que ce soit dans son travail, sa scolarité ou sa vie privée.

Comment la vie quotidienne au sein de ce lieu de création, transmission et production, la rencontre et les échanges avec les artisans d’art et designers du JAD ont-ils orienté tes créations ?

Ces quelques mois au contact des personnes qui travaillent au JAD m’ont permis d’avoir plus de recul sur ce qui les pousse à créer, car nous en avons beaucoup parlé entre nous. La création est une activité assez mystérieuse et intime. Je me demandais comment en parler au public, comment décrire ce qui se passe à ce moment-là. J’aimerais que l’espace d’un instant, les lecteurs et les lectrices puissent se mettre dans la peau de celles et ceux qui créent en permanence, comme c’est le cas au JAD.

Ce n’est pas toujours facile de mettre des mots dessus. Il me semble qu’il y a encore beaucoup d’idéalisation des métiers créatifs, notamment ceux du design et de l’artisanat d’art. En pratique, c’est plus nuancé : toutes les personnes avec qui j’ai parlé au JAD ont décrit des moments de joie intense et de passion, mais également de stress et de doute. C’est inhérent à la création et malgré les obstacles, l’envie de continuer ne les quitte pas. Je voudrais que l’œuvre finale soit le reflet de ces réalités. Je pense qu’il est important de les montrer clairement et de les mettre sur le même plan.

Tu appartiens à l’univers des arts visuels et de l’art contemporain, pour le JAD il était intéressant de pouvoir croiser les disciplines et les regards. Comment 3 mois de vie au JAD, en immersion dans l’univers des métiers d’art et du design, ont pu remettre en perspective le médium sur lequel tu travailles ? Des envies de collaboration, d’expérimentation sont-elles nées de cette résidence ?

La façon dont on parle de nos activités varie selon les milieux : dans les métiers d’art et les métiers du design, il y a des problématiques qui n’existent pas dans le monde de l’art contemporain. Je pense notamment à la notion de fonctionnalité, qui est au cœur des réflexions menées au JAD et à laquelle j’étais relativement étrangère auparavant. Écouter de longues conversations sur ce sujet était passionnant. J’ai également développé une plus grande attention aux matériaux grâce à mes discussions avec les personnes qui travaillent ici : le bois, le cuir, le textile, les matériaux innovants, etc.

De mon côté, j’ai fait des expériences avec les machines que le JAD met à notre disposition, pour transposer des dessins sur des carreaux de faïence qui seront intégrés à mon projet final. Le principe est simple : scanner un dessin réalisé à la main, paramétrer la machine et la voir reproduire la forme initiale sur le support qu’on choisit. De nombreuses questions techniques se posent en fonction des matériaux. Avec les carreaux de faïence, nous avons eu des surprises. Il a fallu faire plusieurs essais avec des réglages différents pour obtenir le rendu souhaité. Quand les paramètres ne sont pas les bons, les lignes sont floues. C’est un problème pour mon travail car quand la machine reproduit des textes, il faut s’assurer qu’ils restent lisibles. J’aimerais aller plus loin dans ces explorations à l’avenir. C’est un exercice de patience et d’intuition.

Propos recueillis par Clara Chevrier

Responsable des publics et de la médiation

Sur la même thématique

Juana García-Pozuelo, rencontre entre l’idée et la main

Lucie Ponard, l'écologie des matériaux

Matière à Penser, un programme d'excellence dédié aux métiers d'art