Marie Levoyet, a singular look at gravure printing

Marie Levoyet is a gravure and intaglio printer. Her expertise, which is rooted in the world of photography and printmaking, is now represented by only a handful of companies in Europe.

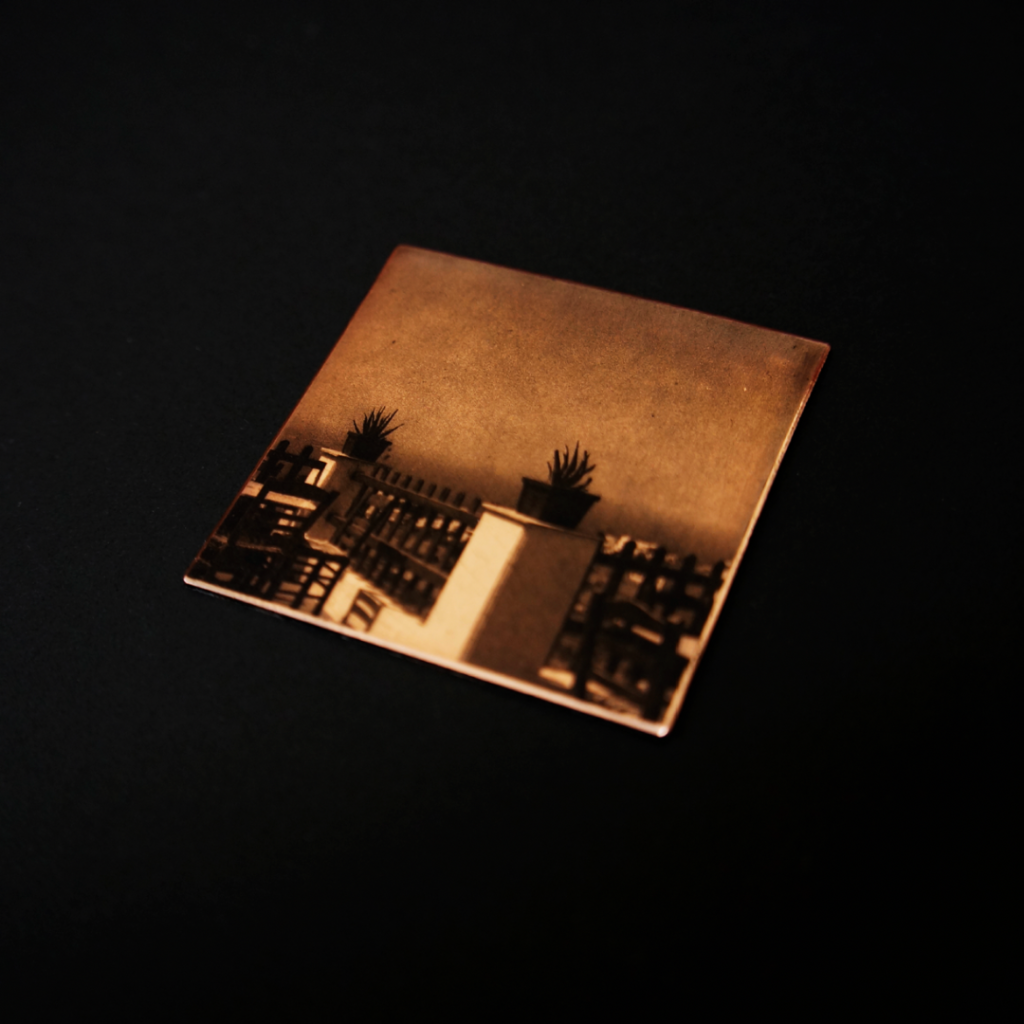

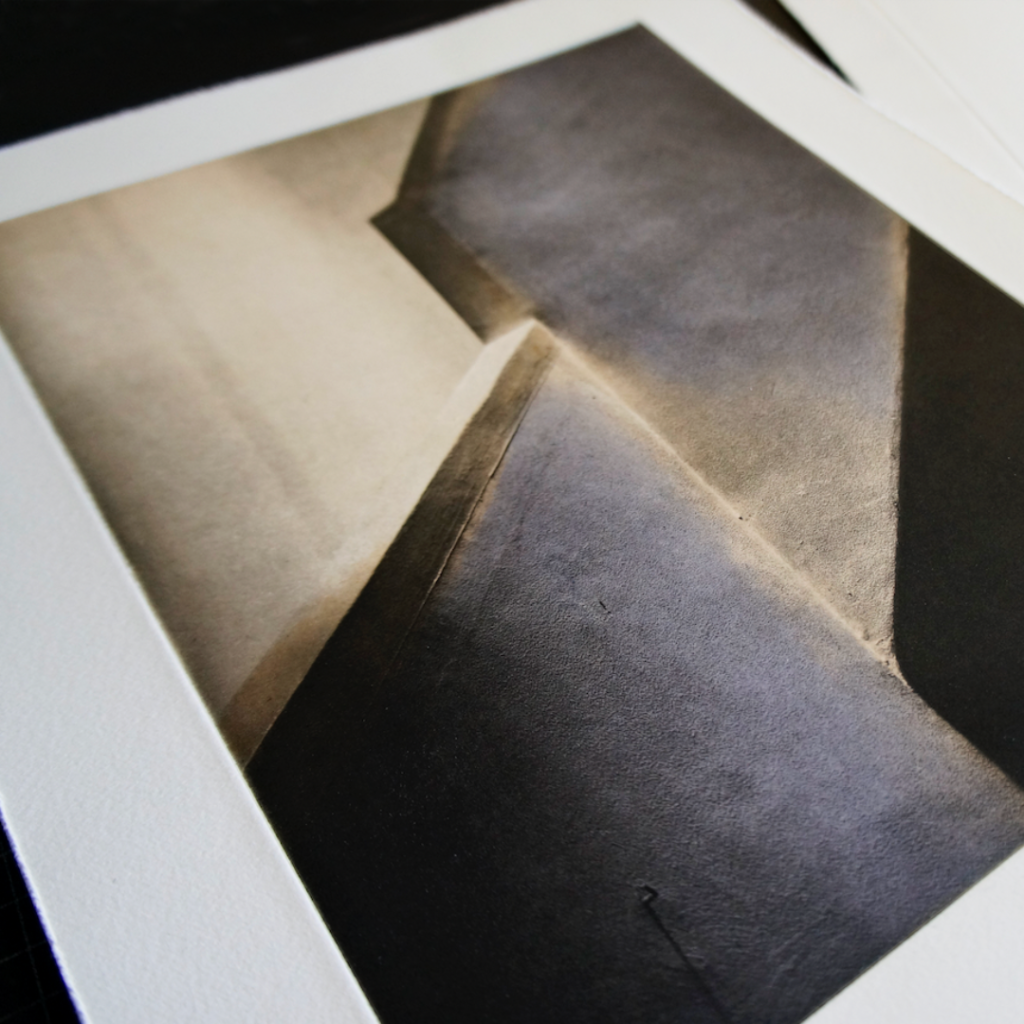

Combining copperplate engraving with the use of photosensitive gelatin, heliogravure is based on a photomechanical process developed in the 19th century, enabling light to fix and reveal the photographic image. Marie Levoyet works in close collaboration with photographers and artists from the contemporary scene.

Settled at the JAD since September 2022, she intends to develop her activity and deepen her research, particularly on the use of color in rotogravure. A studio project encouraged by the Fondation Banque Populaire, from which she recently received a research grant. An opportunity for her to talk about her career, her research and the uniqueness of her profession.

You are one of the six winners of the Banque Populaire Foundation prize: what does it involve?

In December 2022, I had the pleasure of receiving the Banque Populaire Foundation award. Alongside music and disability, the Fondation Banque Populaire has been supporting arts and crafts since 2013. This year, the jury - chaired by Gérard Desquand, heraldist engraver and Master of Art - selected six craftsmen.

This award provides us with financial and human support over one to three years, so that we can develop our activity and our workshops can explore and take new paths. Above all, the grant supports research projects. In my opinion, this is what makes it such a fine prize: by enabling workshops to open new doors, it provides real support for creation and the renewal of know-how.

In addition to supporting my studio project in its entirety, this grant will enable me, more specifically, to develop my research into color gravure.

How do you approach your research into color? What are the issues involved?

Rotogravure itself is a rare skill, but four-color rotogravure is even rarer: to my knowledge, there are very few workshops specializing in color. These techniques are being lost and are disappearing, even though the demand from photographers is very real. So there's a real need to preserve know-how.

But above all, this approach has its origins in my desire to go further and further in the work of interpretation, by reinforcing direct contact with the image: with the sensation and materiality of the image. To offer this interpretation as close as possible to the photographed image, my research focuses in particular on pigments. My ambition is to make and use pigments composed of elements from the place where the photographs are taken: earth, sand, which I would collect in the field, alongside the artists and photographers I work with.

The use of colored inks also represents a technical challenge. The use of color to produce a four-color gravure requires greater precision in working with the copper plate - mainly in cutting the copper - which pushes me to deepen and revisit the gestures and techniques usually employed.

How did you develop your relationship with images and color? What is the story behind your encounter with gravure printing?

Originally, I did a BTS in textile design, where I studied weaving techniques, as well as dyes and patterns, which echo my current research into color. But I was still a long way from rotogravure or even printmaking in general.

My encounter with this technique came unexpectedly at the end of my training in textile design: the turning point came when I met, by happy chance, Fanny Boucher, Master of Art and representative of gravure printing in France. I spent a few weeks as an intern in her workshop, and never left.

As with many rare skills, there is no training course as such for gravure printing. So I was able to continue my training with her, thanks to a number of schemes designed to support artistic crafts and encourage the transfer of skills. The Prix de perfectionnement aux métiers d'art de la Ville de Paris [now the Prix Savoir-Faire en Transmission, then the Maître d'Art - Elève program enabled me to learn the intaglio printing technique and then that of rotogravure, while at the same time setting up my own workshop in 2018.

What attracted you to this very special technique?

What first attracted me to gravure printing was the fact that it was taught to me by Fanny. Our relationship and the passion she was able to pass on to me for her craft were key factors in my career.

Today, I'm fascinated by the central role played by exchanges with artists. In the course of each project, we discover precise, cutting-edge universes that are so personal and different from one another. They are mostly contemporary photographers, but sometimes painters or visual artists as well. They come from Georgia, Luxembourg and the United States. Each has his or her own way of working, which I try to grasp: understanding the atmosphere of the photograph, the context of the image, the sensations, sounds and memories that the artist associates with it. All these elements then enable me to interpret the image and translate it through the engraving of the copper plate and the choice of inks.

Finally, the empirical dimension of this science makes rotogravure a highly enriching technique. The result depends on a multitude of parameters, so we have no choice but to constantly question the way we do things. And then, at the end of the process, there are the small moments of grace, when you feel you've touched the image in all its sensoriality and materiality. Gravure printing has a powerful symbolic dimension: the matrix and the print fix an image in time, while the technique reveals its rough edges and humanity.

Since you moved to JAD, how has your proximity to other creators nurtured your work?

Exchanges and collaboration with JAD's craftsmen and designers are an essential lever for research and creation, helping to preserve and renew know-how. For me, it's very inspiring to see other designers looking at rotogravure, the photographic processes it uses and the materials associated with it. These singular perspectives open up new horizons for me, enabling me to explore the potential of this craft and continue to redefine its boundaries.

Interview by Brune Schlosser

In charge of cultural and heritage projects at INMA

and INMA correspondent at JAD

Photo credits: © Eric Chenal - © CD92/Julia Brechler

On the same theme

Juana García-Pozuelo, rencontre entre l’idée et la main

Lucie Ponard, l'écologie des matériaux

Matière à Penser, un programme d'excellence dédié aux métiers d'art